Dual Class Contracting

Dual-class structures are one of the most controversial topics in corporate governance. Many find them objectionable, on the grounds that they violate fundamental principles of shareholder democracy, reduce accountability of managers, and distort the controller’s incentives to create value for all shareholders. Others, in contrast, believe that dual-class structures protect the founders’ entrepreneurial vision from myopic market pressures, improve the controller’s incentives with respect to risk-taking, and strengthen the managers’ bargaining power vis-à-vis buyers of the company. The debate remains unresolved.

The choice between dual-class and single-class structures has been the subject of academic and policy debates for many years. But voting inequality is a spectrum, not a binary choice. A dual-class structure that allows the controller to have a majority of votes with only 4.8% of the shares (such as the one chosen by Pinterest, for example) is much more unequal than a dual-class structure that requires the majority shareholder to have at least 35% of the shares (such as the one adopted by Cognizant). Similarly, a dual-class structure that may last for the entire life of the founders (such as the one chosen by Google, for example) or in perpetuity (such as the one chosen by Facebook) is much more unequal than a dual-class structure that expires after five years (such as the one chosen by Groupon). If voting inequality matters, then the choice between more unequal and less unequal structures must be taken seriously.

Unlike the “categorical” choice between dual-class and single-class structures, however, the “continuous” choice of specific levels of voting inequality remains little studied. How much variation and customization are there within dual-class structures? What is the contribution of the various market players to the final shape of these structures? Do real-world dual-class arrangements adapt to different characteristics of companies and controllers, as the textbook model predicts? How do dual-class structures evolve and what might explain the patterns of change or persistence?

This Article sheds light on these questions by examining both quantitative and qualitative evidence on initial public offerings (IPOs) of U.S. dual-class companies. I analyze and discuss a hand-collected sample of dual-class charters adopted at the IPOs by U.S. nonfinancial companies, as well as the findings from a survey of more than three dozen law firm partners with expertise on dual-class IPOs. The charters included in this study represent a comprehensive sample of all dual-class IPOs by U.S. nonfinancial companies from 1996 to 2022, totaling 293 corporate charters. Respondents to the survey and the follow-up interviews are senior IPO lawyers, working at elite law firms that have assisted more than two-thirds of dual-class issuers between 2013 and 2022.

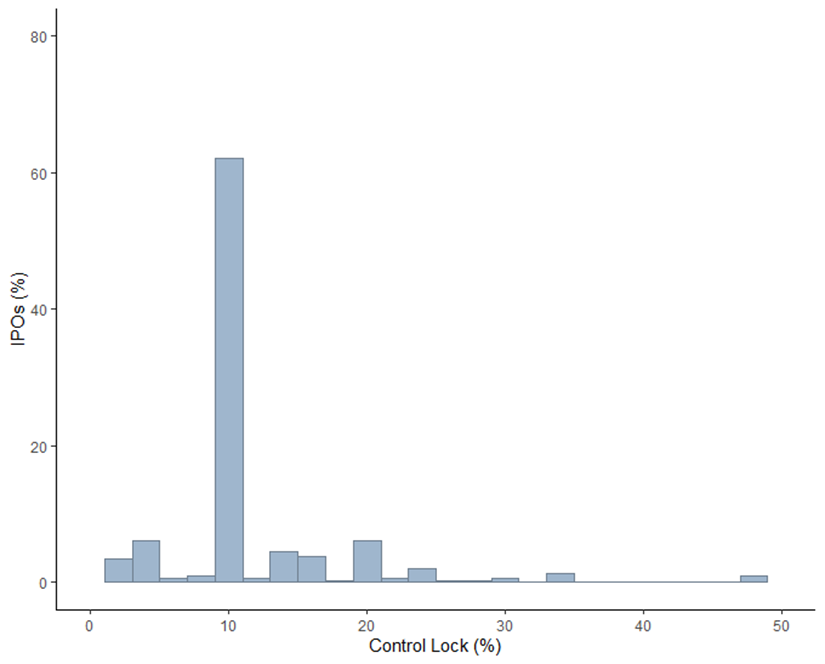

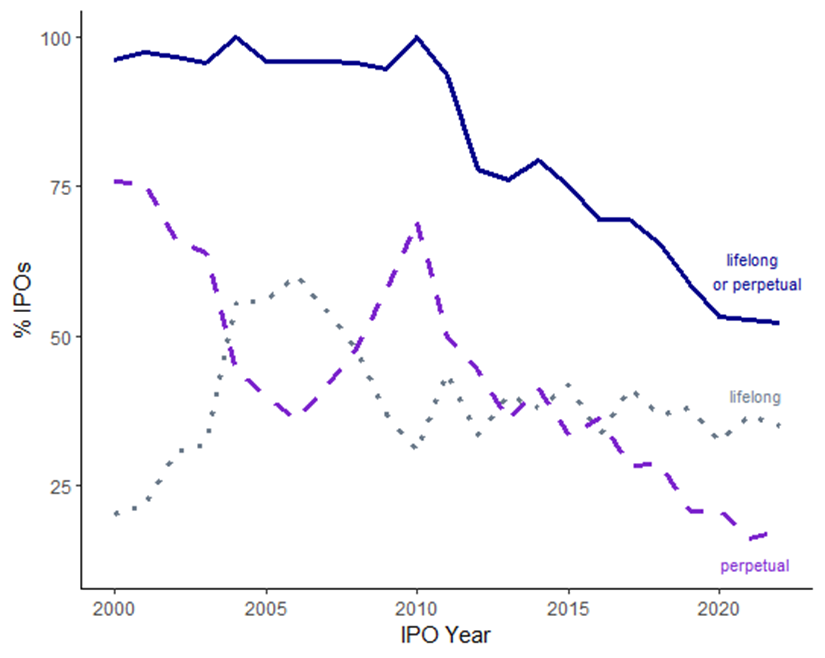

The Article has three goals. The first goal is to map the dual-class landscape and to document variation and customization of voting inequality and dual-class charters across almost 300 companies and three decades. I measure voting inequality in two dimensions: degree and duration. I measure the degree of voting inequality by calculating, for each dual-class charter, the smallest percentage of common stock that a high-vote shareholder must own to have 50% of the votes (building on a methodology first proposed by Professors Lucian Bebchuk and Kobi Kastiel). I call this metric the “control lock.” I measure the duration of voting inequality by calculating the combined effect of charter provisions that allow high-vote shareholders to keep a dual-class structure in place over time.

One important finding is that, despite a broad spectrum of possible tailor-made options, most dual companies choose similar or identical levels of voting inequality. In theory, dual-class companies can choose a control lock from slightly above 0% (extreme inequality) to slightly below 50% (very low inequality). Furthermore, they can choose whatever duration of voting inequality they think is most appropriate for their company, from a few months to the entire life of the corporation. But in practice most companies conform to strikingly similar patterns.

Degree of Voting Inequality

Over the entire 27-year period, 62% of companies chose a control lock in the very narrow range between 9% and 10%, and less than 7% chose a control lock greater than 20%. Furthermore, between 1996 and 2010, 96% of dual-class structures had a potentially lifelong (27%) or perpetual (69%) duration; then the landscape changed dramatically and between 2011 and 2022 only 58% of dual-class companies chose lifelong or perpetual structures. Perpetual structures became quite infrequent (21% in the 2011–2022 period, 13% in 2021–2022).

Duration of Voting Inequality Over Time

Interestingly, with limited exceptions, degree and duration of voting inequality are not statistically associated with characteristics that, according to the previous literature, predict the categorical choice between dual-class and single-class structures. In other words, it seems that the continuous choice is largely unanchored from the characteristics that affect the categorical choice.

The second goal is to reconstruct the “contracting process” that shapes dual-class charters. In a 2006 article, Professor Michael Klausner observed that the fact that “corporate contracts reflect a high degree of uniformity” rather than “fulfilling their contractarian role as the locus of innovative and customized corporate contracting” warrants “at least some rethinking of the contractarian theory…” Even Klausner, however, considered dual-class structures as an exception to such a uniform landscape and one of the very few instances of “deliberate contracting. . . in the drafting of corporate charters.”

But what counts as “deliberate contracting”? The textbook story is that corporate insiders “bargain” with the investment banker, who acts as representative of the public investors, and the governance features ultimately chosen by the company tend to maximize the joint surplus of insiders and public investors, given the individual characteristics of the company.

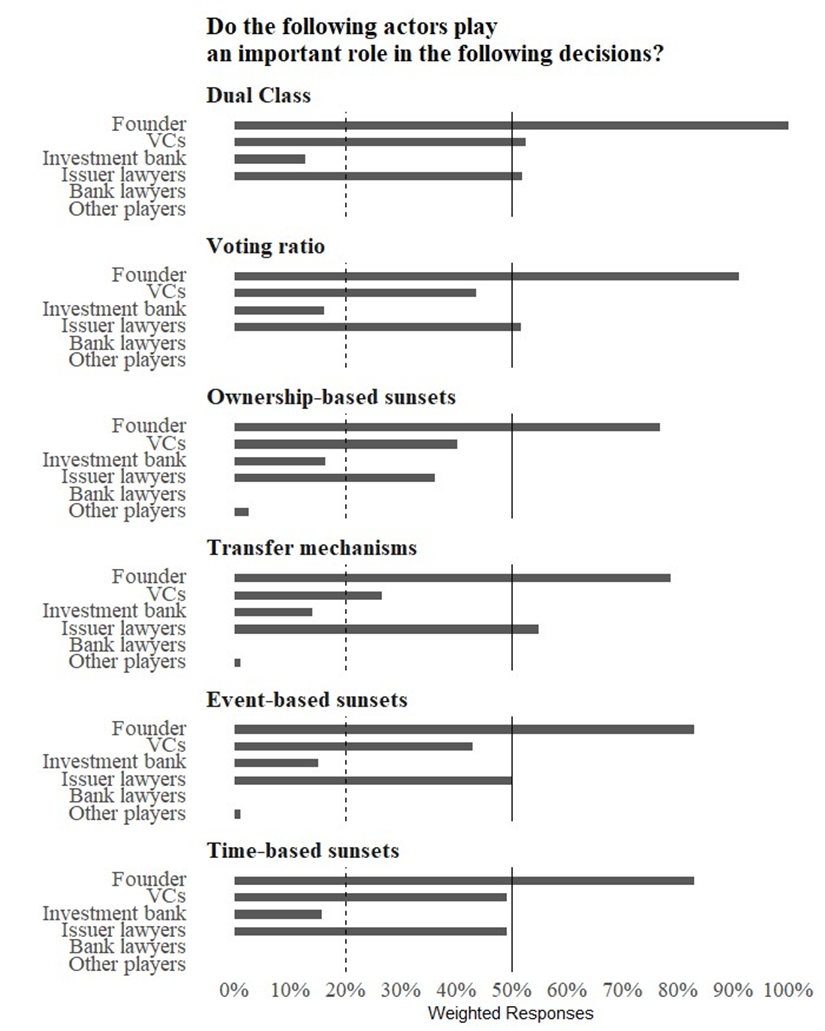

However, the real-world picture painted by the senior lawyers who participated in the survey and the follow-up interviews shows that the pricing of dual-class features is surrounded by high uncertainty, and companies tend to comply with “market norms” rather than tailoring the levels of voting inequality to their specific circumstances. Indeed, neither investment bankers nor investors are perceived to play an important role in designing dual-class structures, whereas founders, venture capitalists (VCs) and—surprisingly—issuer lawyers are believed to play a significant role.

Both issuer lawyers and investment bank lawyers perceive the role of issuer lawyers as crucial in shaping or reshaping the founders’ preferences based on the existing “market practice.” This story is at odds with the textbook model: contrary to this model, in the real world, the main preoccupation of IPO insiders has less to do with optimizing dual-class features and more with conforming to prevailing norms, and lawyers seem to play the very important role of conservators and perpetuators of these norms.

Role of Market Players in Dual-Class Design

The third goal is to try to reconcile this picture with the standard theories of corporate contracting. The “classic contractarian theory” of the corporation argues that pre-IPO owners internalize the effects of charter provisions on firm value, and therefore corporate charters will tend to include value maximizing provisions. Under this view, the level of voting inequality should be a function of company characteristics and founder characteristics. It is plausible, however, that company and founder characteristics vary significantly across firms; therefore, the low variation in voting inequality among real-word dual-class companies is puzzling. It is possible, in theory, that the 9%–10% control lock and an unlimited duration (before 2011) or a mix of lifelong and 7–to–10–year duration (from 2011) are optimal for most dual-class companies. However, the fact that companies with different characteristics do not choose tailor-made solutions more frequently is suspicious.

More recent work has provided richer and more nuanced versions of the contractarian theory. I call them “modern contractarian theories.” On the topic of standardization and customization in corporate governance, the main insights of the modern contractarian theories concern the role of learning and network externalities and of agency problems. But do these mechanisms persuasively explain dual-class norms? I will argue that, with respect to dual-class structures, these models are much less compelling than in other cases.

The learning externalities hypothesis relies on the assumption that companies that adopt standard terms save on drafting and other advisory costs and reduce legal uncertainty. But customizing dual-class structures does not seem to require significant drafting efforts or to add legal uncertainty. Dual-class companies can very easily alter the degree or duration of voting inequality with very little cost and virtually no risk of ambiguity or legal uncertainty, yet, in most cases, they choose not to do so.

The agency problem hypothesis relies on the assumptions that the lawyers’ work is assessed based on good or bad outcomes rather than on its intrinsic quality; that a bad outcome has a disproportionately larger cost for the lawyer’s reputation when the lawyer chooses a customized contract term rather than a standard contract term; and, therefore, lawyers choose standard terms even when they are not in the best interest of their client. In the case of dual-class structures, however, the “standards” concern substantive features—such as how large the voting power asymmetry will be and for how long this asymmetry can persist—rather than mere technical legal terms. Agency theories of contractual standardization typically deal with technical legal language, which is not easily understood and assessed by the clients. Here, by contrast, founders, VCs, company directors, and institutional investors can accurately observe the level of voting inequality chosen in the IPO charter and act accordingly.

Given the limits of classic and modern contractarian theories in explaining the real-world dynamics of dual-class contracting, we need a richer story. In the last two sections of the Article, I will sketch a conjecture that draws from different literatures on social norms (by sociologists, economists, and legal scholars). Briefly stated, the conjecture is as follows. In dual-class contracting, “market norms” play an important role alongside individualized contracting. Indeed, the market practice in dual-class IPOs possesses certain essential characteristics of social norms: compression (i.e., low variation), stickiness (i.e., persistence over time), and the so-called punctuated equilibrium (i.e., long period of stasis followed by rapid change). Furthermore, the key insiders surveyed and interviewed for this Article seem to treat dual-class market practice as norms—standards that one ought to comply with even if the underlying price-maximization rationale is unclear. Finally, the emergence of these norms resembles random mutation rather than rational design, with some important innovations appearing to have been spurred by the deliberate actions of individuals and organizations, akin to the role of “norm entrepreneurs” in changing social norms.

If the market norms conjecture is, as I believe, an accurate explanation of an important part of dual-class contracting, the policy debate on dual-class companies should focus on understanding the process shaping these norms, starting from the recognition that some aspects of this process might be different from what classic and modern contractarianism predict. To begin with, contrary to the classic contractarian theory and the learning externalities theory, we should not dismiss the possibility that the prevailing dual-class norms may be bad for investors. Furthermore, contrary to the agency theory, the lawyers are not to be blamed for this phenomenon: market norms exist because the dual-class IPO process is embedded in business and social relationships. Finally, we should envisage the role of the regulator in this space neither as a passive spectator (as standard contractarian accounts suggest) nor as an active designer of optimal voting structures (as anti-contractarian accounts suggest), but rather as a facilitator of tailor-made contracting and norm innovation.